Document Embedding Basics

In a previous post I talked about how tools like word2vec are used to numerically understand the meanings behind words. In this post, I’m going to continue that discussion by describing ways we can find numerical representations for whole documents. So, I’ll be assuming you’re already familiar with the concept of word embeddings.

Why do we need document embeddings?

Many real-world applications need to understand the content of text which is longer than just a single word. For example, imagine you wanted to find all the political tweets on twitter. Well, the first thing you might try is to make a big list of all the words you felt were “political.” You might list “president,” “congress,” and “senate” and simply search for any tweet that contained those words.

Of course, this would work for many cases, but you would miss tweets that don’t use the words on your list. For example, image a tweet that used a congressman’s name, but didn’t actually write the word “congress.” Also, you would get tweets that use a word on your list, but aren’t really what you’re looking for. For example, I just learned that one should refer to a group of small colorful lizards as a “congress of salamanders.”

Another application that can be very important is that of detecting duplicates. For instance, when you post on Stack Overflow, there is a feature which attempts to find questions similar to the one you are asking. If we simply try to look for the number of words shared between posts then we will have very similar problems to the twitter example above.

In order to solve these problems we are going to use the concepts from word embeddings to learn a vector representation of each document. This will give us an approximation of that document’s content, and that will give us a sophisticated way to compare and classify text.

How do we get a document’s embedding?

Of course, there are many different ways to find a vector representation of a document. Here we are going to summarize three, the BOW method, the centroid method, and the doc2vec methods.

Bag Of Words

The simplest embedding is still the Bag-Of-Words method. Like before, if we have $|W|$ different words in our corpus, then we will need a vector $R$ of length $|W|$ to represent our document. We assume that each word has some index $i$, so our vector $R(d)_i = \text{# of times $w_i$ occurs in $d$}$.

Comparing documents by their BOW vectors is a start, but we sill have all of the same problems we talked about above and in the previous post.

Centroids

If you have been following closely, you probably already thought of this. If we have a word embedding $R(w_i)$ for each of our words $w_i \in W$, then why not just represent a document as the average of all of its contained words?

$$ R(d_j) = \frac{\sum\limits_{w_i \in W_j} R(w_i)}{|W_j|}$$

This method actually works pretty well, especially for smaller documents1. If we think about comparing tweets, like we did above, then we would expect the vectors of two political tweets to be close to each other. It doesn’t matter if these tweets don’t use exactly the same words, one might be talking about a prominent politician and the other might be talking about a specific policy, but they both will likely use words that often occur in a political context. If one tweet were really talking about a congress of salamanders, then we would expect vector for salamander would move that tweet’s centroid further away from all the political tweets.

So whats the downside? Well, just like BOW, we lose the ordering of the words. This means “cats eat mice” and “mice eat cats” will have the same centroid. Additionally, we still fail to disambiguate the same word being used in different contexts. This means that “I swung the bat” and “I swung at the bat” will only differ slightly.

Doc2Vec

Yup, the moment problems arise, we make a new blank2vec. Doc2Vec2 learns vector representations of paragraphs along with word representations. By combining these ideas, Doc2Vec embeddings outperformed many of the other methods that were around when it debuted1.

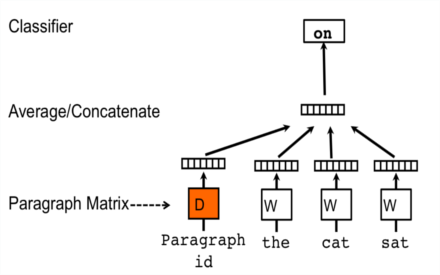

If you remember word2vec, we learned the representation of a word by looking at its surrounding context. Doc2Vec adds a new vector into this context, representing the paragraph. In the same way word2vec refers to both the CBOW and skip-gram method, doc2vec refers to two methods, each with their pros and cons.

Distributed Memory Model (PV-DM)

In PV-DM, each time we attempt to predict a word given it’s context, we introduce a vector corresponding the paragraph from which that window was taken. Although it would require a little more engineering, this is the mechanisms we might use if we wanted to disambiguate “I swung the bat” and “I swung at the bat”. More directly, the paragraph vector helps inform the model as to which concepts are most likely to be discussed within the current window.

Le, in the original paper2, says that this vector provides memory, because the vector will change based on the words present in other parts of the same paragraph. Conceptually, imagine a paragraph discussing a man and his dog. Because of the paragraph vector’s influence, the model will be more likely to succeed when attempting to fill in the blank in: “the man walked his ____.”

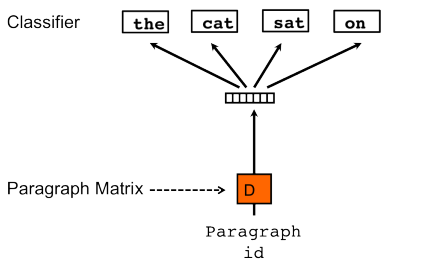

Distributed Bag of Words (PV-DBOW)

Another way to find these vectors is the PV-DBOW method, where a paragraph vector is used to predict a number of words which have been randomly sampled from its text. Although this model starts with a single element and predicts a number, it seems to resemble the skip-gram method in word2vec. This is a bit inaccurate because the training process does not consider the ordering of these predicted words. Additionally, in comparison to PV-DM, this method is computationally less expensive.

Le’s paper states that the PV-DBOW method tends to produce poorer results than the PV-DM method, but when used in combination with PV-DM provides more consistent results.

Comparison and Conclusions

So when doc2vec initially premiered, there was some controversy as to whether it could really outperform the centroid method. So, Lau and Baldwin performed an extensive comparison between these methodologies across different domains1. The general consensus what that different methods are best suited for different tasks. For example, centroids perform well on tweets, but are outperformed on longer documents. I highly recommend this paper to anyone looking to include some of these techniques into their own work.

When comparing these methodologies, I’m referring to this great paper. ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎

Doc2Vec was also worked on by the original word2vec author, and it is also a very good paper ↩︎ ↩︎